I attended 5 days of ICLR Workshop - Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning remotely from 2020-04-26 to 2020-04-30. I was able to attend majority of the talks for the first day of the conference, and on and off throughout the rest of the conference. I'll use this post to share some of my general thoughts and observations on the topic of applying machine learning to help with climate change.

(If you're interested, here are the notes I took from the conference.)

- Day 1 (Main Workshop)

- Day 2 (Energy Day)

- Day 3 (Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use (AFOLU) Day)

- Day 4 (Climate Science and Adaptation Day)

- Day 5 (Cross-cutting Methods Day)

Overview

The machine learning breakthroughs for the past 10 years has been primarily focused on the bits world, and more and more industries are leveraging machine learning for their competitive advantage - marketing, customer segmentation, recommendation engine, personalization, anti-abuse / anti-fraud, etc. Breakthroughs in deep neural networks applied to computer vision and NLP model allow us to achieve paradigm-shift improvement in machine translation, computer vision, conversational AI... etc. All of these progresses are very exciting.

On the other hand, the climate change issue is, inherently, a challenge in the atomic world. It was caused by CO2 molecules that we pump into the atmosphere by billions of tons per year, from a wide collection of economic activities. Therefore, if machine learning were to make an impact to climate change, it would have to render effects in the physical world. Having attended the ICLR Workshop on "Tackling Climate Change with Machine Learning" for the past five days, I want to organize my thoughts in this post on applying machine learning to the issue of climate change.

There is no single field of "machine learning & climate change"

Because anthropogenic climate change is a product of all human's economic activity, it should be obvious that there's no single field called "tackling climate change with machine learning". This can be seen from the multi-day ICLR conference: it was broken into "Energy", "Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use", and "Climate Science and Adaptation". The 100+ page arxiv paper on "Tackling machine learning with climate change" is even more detailed - it includes sections on "Electricity Systems", "Transportation", "Buildings & Cities", "Industry", "Farm & Forests", "CO2 Removal", "Climate Prediction", "Societal Impacts", "Solar Geoengineering", "Individual Action", "Collective Decisions", "Education", and "Finance". This really goes to show that the climate change is a multi-faceted problem that encompasses all economic activities, and machine learning has a potential to make an impact in a variety of applications that are related to climate change.

Willingness to engage with stakeholders and domain experts is key

Speaker after speaker in this conference have highlighted the importance of working with stakeholders and domain experts. Of course, there are many layers of possibilities for machine learning professionals to collaborate with domain experts. Successful and closely-knitted collaborations take a long time to build. Here are some questions for ML practitioners to think about:

- How do you find climate change domains that ML can help?

- How do you find domain experts / stakeholders who would be willing to work with you?

- How do you make sure the incentives are aligned? For ML researchers, the primary driver is oftentimes predicated on novel methods and/or novel applications, which may not be what the domain experts need at the time. For example, Dan Morris from Microsoft brought up that while ML researchers may be interested in the novel problem of species detection from cameras, conservation ecologists dealing with video footages from the field may be more interested in tasks that ML researchers consider "mundane", like being able to tell whether the video footage of detected movements contain a human, vehicle, or wild animals.

- In the initial phases of the collaboration, even getting to the point of speaking the same language takes a long time. John Platt (Google) brought up this from his experience collaborating with fusion researchers.

- How are your ML models meant to be used in the real world? (See the "Making impact with your ML model is even thornier" section below.)

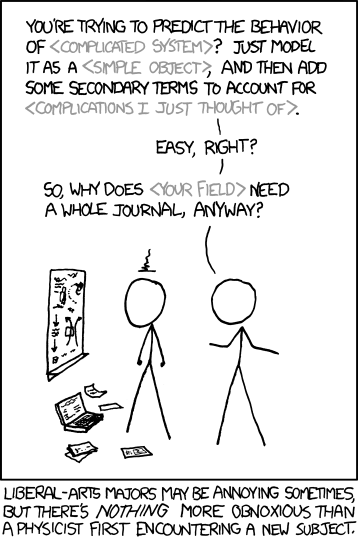

Machine learning has its limits

The multi-faceted nature of climate change mitigation and adaptation also means that the potential for machine learning to make impacts is uneven across various sectors, and we as machine learning professionals have to be cognizant of the limits of machine learning. There are sectors that dealt with heavy-duty industrial processes that are extremely carbon intensive (industrial heat for concrete and steel making, trans-ocean shipping, etc) and difficult to electrify unless there are significant hardware breakthroughs. Likewise, the sophistication in remote sensing to monitor carbon emission, deforestation, and habitat loss would only be able to make a real impact on climate change if the monitoring result were able to be followed-up by behavior change on the ground through policy support and the right alignment of stakeholder incentives.

For some problems, machine learning can only have a tangential effect at best. Even for problems that machine learning can play a pivotal role, it's important to recognize that the job is not done just by fitting a state-of-art machine learning model. (See the "Making impact with your ML model is even thornier" section below.)

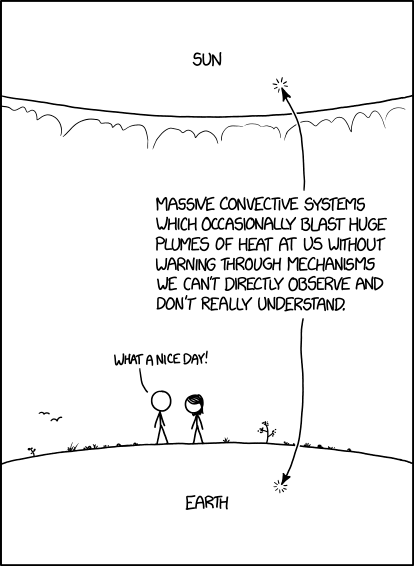

We are not spending nearly enough resources at our understanding of our physical world at large

During the conference, Lucas Joppa, Chief Environmental Officer from Microsoft, made a succinct point and a passionate plea that we are spending vast amount of our attention and resources on "how to find the closest Starbucks that are still open", and understand embarrassingly little about the vast planet that we are in. The Microsoft speakers from this conference highlighted their AI for earth efforts that partners with non-profits and startups to help with environmental initiatives, and Microsoft definitely stood out in their environmental commitments to go carbon negative by 2030.

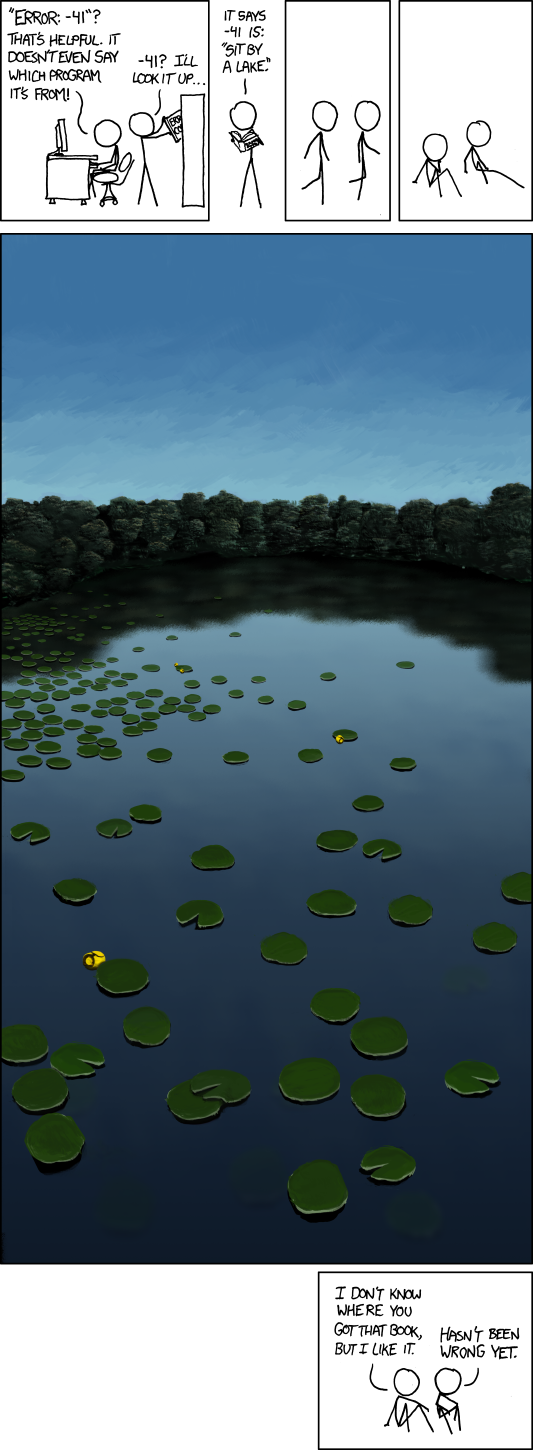

New data sources are coming online; yet, there are still many unmet needs

Remote sensing through satellite imagery is probably one of the prominent examples. From the Landsat satellite in the 90s to modern satellite imagery, the spatial resolution has been greatly improved from 30m to 3-5m resolution, which enables the researchers to do things that they weren't able to do previously. However, there are still unmet needs in the data. For example, some of the agricultural applications have very specific requirements for the remote sensing data - not only does it have to have the right spatial resolution, it also has to be acquired during the growing season of the crop.

Another example I found interesting is on the application of solar forecasting. Jack Kelly (Open Climate Fix) highlighted the need to have very high spatiotemporal remote sensing data for cloud covers near solar cell arrays, which is currently an unmet need. Even for simulations, there are no good "3D data of point clouds" that researchers can use to build a simulation on.

Small data / sparse label problem may require new algorithms (or algorithms that may not be a obvious choice)

Multiple speakers highlighted the data problem that they are facing in their respective fields - labeled data are by and large fairly sparse, and it's quite difficult to fit a good model on small data using traditional approaches. Therefore, approaches such as transfer learning, semi-supervised learning, unsupervised learning etc, could be useful here. (Andrew Ng has made a similar point regarding transfer learning at the NeurIPS workshop last year.)

Also, think very carefully about the model type for the problem. Deep neural network models have seen a lot of attention in recent years, but in a setting where you don't have a lot of label data, neural networks may not always work better than traditional models, even for datasets that it traditionally does well (like satellite images). For example, Victoria Coleman (Atlas AI) mentioned that in a crop classification problem her team worked on, random forest can achieve equal or better result as deep neural networks.

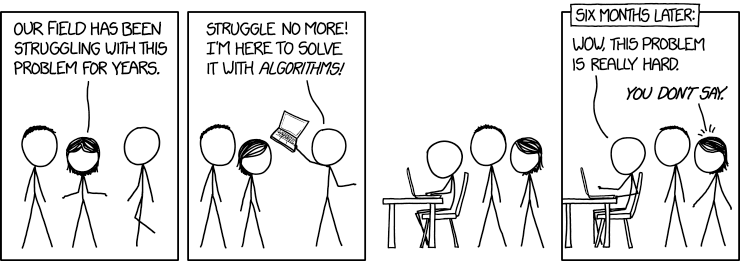

Evaluating model that makes prediction in the physical world is a thorny problem; making impact with your ML model is even thornier

Given that information that can be gleaned for climate change domains is often incomplete and sparsely labeled, researchers will need to think carefully how to evaluate and validate their model in the field. There were a few interesting examples shared by Catherine Nakalembe (Univ of Maryland) working in agricultural applications - knowledge that they obtained from the field can, in turn, help them recognize their biases and misunderstandings about their data, and refine their models accordingly.

Furthermore, if the goal of your machine learning model is to make impact in the real world (through data-informed policy decisions, behavior change for the stakeholders), it is really important to understand how your model is meant to be used to influence change in the world. There were a couple examples that left an impression for me:

- Jack Kelly (Open Climate Fix) brought up his experience working with UK National Grid ESO. A lot of the grid operators still relies on human-in-the-loop to implement changes, so if your sophisticated optimization algorithm relies on a human pressing buttons five times a second, it will most certainly not be implemented.

- There's also issue with convincing your stakeholders (policy makers, infrastructure operators, etc) that your model is trustworthy, and worthy to be put into "production" to influence the physical world. ML models often have had a hard time being "believed" by domain experts, unless there's way to use models on synthetic data and show that the models matches with what the experts agree on physics-based principles.

- Another challenge for influencing policy makers is that there's no way for non-technical experts (e.g. policy makers) to really become "co-equals" with ML researchers, unless the non technical stakeholders have way to "play / tweak" models themselves without writing code. This may involve more efforts on building simplified version of your model, and allow non technical people to use it with a UI to play with different scenarios. This takes more time (and different sets of expertise) than what ML researchers are used to.

- Max Nova (SilviaTerra) highlighted the "misaligned incentive" problem. His startup partners with Microsoft AI for earth to use remote sensing to monitor deforestation, but for that knowledge to actually decrease deforestation, it would need to involve stakeholders in developing countries and give farmers an alternative to chop down trees. If there isn't a way to pay people for not chopping down trees, they will continue to chop down trees for timber, agriculture, etc, because it is clear that they can get paid for that.

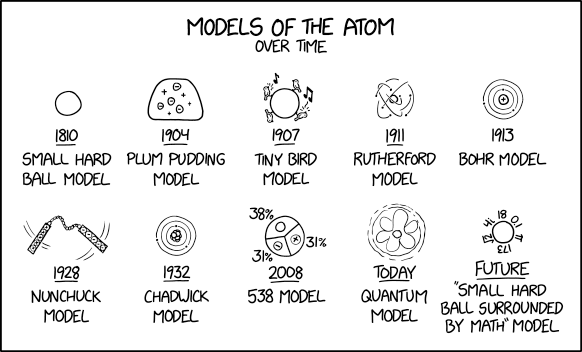

Blending machine-learning-based and physics-based models

There are a couple talks that highlight the idea of incorporating physics and geospatial understandings to underpin the model. This could mean using physical simulations to bootstrap your training set (e.g. simulate buildings and its behavior), incorporating physics equations in the implicit layers of your neural networks, or use geospatial distributions as featurization methods in transfer learning (e.g. Tile2Vec). There's a lot of interesting things to learn and do in this area, and I will be excitedly watching its development!

Final thoughts

Whew! That was longer article than I planned to write, and thank you for reading it till the end. I will close this with the quote from Tackling climate change with machine learning paper, because I don't think I could have said it better myself:

Climate change is one of the greatest challenges facing humanity, and we, as machine learning experts, may wonder how we can help. Here we describe how machine learning can be a powerful tool in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and helping society adapt to a changing climate. From smart grids to disaster management, we identify high impact problems where existing gaps can be filled by machine learning, in collaboration with other fields. Our recommendations encompass exciting research questions as well as promising business opportunities. We call on the machine learning community to join the global effort against climate change.

[...]

We emphasize that machine learning is not a silver bullet. The applications we highlight are impactful, but no one solution will “fix” climate change. There are also many areas of action where ML is inapplicable, and we omit these entirely. Furthermore, technology alone is not enough – technologies that would address climate change have been available for years, but have largely not been adopted at scale by society. While we hope that ML will be useful in reducing the costs associated with climate action, humanity also must decide to act.

I sincerely hope that more machine learning professionals will join the fight to solve the climate change, the problem of the 21st century. While COVID-19 has been an immediately pressing matter for the entire world in the past 4 months, climate change is a problem that is even longer-lasting, and we need all of world's brightest mind we can get!

Comments

comments powered by Disqus